Nov 21

2019

Solving Today’s Interoperability Gaps

By Drew Ivan, EVP of Product and Strategy, Rhapsody and Corepoint Health.

Healthcare is home to some of the most mind-blowing technological advances when it comes to diagnostics and therapies. At the same time, the healthcare system is responsible for many of the most head-scratching operational difficulties related to standard IT processes, such as those involved with moving data from one system or site to another. The same industry that successfully deploys remote-controlled surgery robots to heal a patient also struggles to send a discharge summary to a physical therapist for the same patient.

How can we explain this apparent paradox?

A Model of Interoperability

The simple answer is that interoperability in healthcare is a journey, not a destination. The question “why haven’t we solved interoperability?” assumes that interoperability is a one-time problem, when in fact the systems, standards, and data flows that constitute interoperability are constantly changing as the underlying patterns of treatment and reimbursement change.

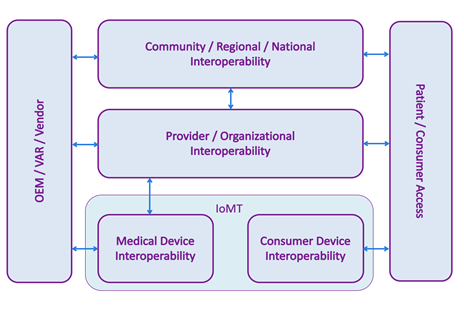

Interoperability today spans more systems and settings than ever before, and “interoperability” means different things to different audiences, so it’s worth taking a moment to ponder the modern interoperability landscape. The following model is an expansion of one suggested by the National Academy of Medicine[1].

Interoperability today spans more systems and settings than ever before, and “interoperability” means different things to different audiences, so it’s worth taking a moment to ponder the modern interoperability landscape. The following model is an expansion of one suggested by the National Academy of Medicine[1].

In the center, provider, or organizational, interoperability indicates data flows within a single organization, typically a hospital or hospital system. This has historically been dominated by HL7 v2 transmitted over a TCP connection on a private network, although other standards and technologies are also used.

At the top, community, regional, and national cross-organizational Interoperability refers to communication of healthcare data across different organizations, for example ACOs, HIEs, and provider-to-payer data flows. In this part of the model, we often see IHE style integrations that exchange entire patient records in a single, secure transaction over a public network.

At the bottom, the Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) is divided into two parts: medical device interoperability, which concerns devices used in a clinical setting, and consumer device interoperability – commercially available devices marketed directly to consumers, such as fitness devices and in-home monitors.

On the left, healthcare IT vendors need to enable their products to interoperate at different levels of the interoperability model, depending on which markets they serve. For example, an EHR vendor will need its product to send and receive HL7 v2 messages in order to participate in the organizational interoperability space.

On the right, we are seeing an increased demand for patient or consumer access to their data, whether it is from a fitness device, a hospital’s EHR, or a payer’s disease management system. Integration in this box is often accomplished using APIs, including FHIR.