Apr 28

2015

Fearful Patient Engagement

Guest post by Judy Chan, president, HealthPro Consulting.

Two big communicable disease scares—Ebola and measles—gripped the attention of the general public recently. They did so with enough strength that the average person on the street spoke out and demanded that actions be taken to protect themselves and families. It was virulent on social media. The total count of Ebola deaths at the end of last year was 5,021 worldwide. The CDC reported 10 Ebola cases treated in the U.S. and two patients died as of January 2015. There were 121 total measles cases in the U.S. this year in 17 states. All but 18 of the measles cases were because of an outbreak that spread from Disneyland in California.

What is remarkable is that these two infectious diseases affected a total of less than 200 people across the nation. Yet it triggered a vigorous response from masses of people who were afraid that they could contract Ebola when the actual chances were significantly lower than dying from a lightening strike. The spread of measles among children erupted into online wars between the vaccinated and unvaccinated.

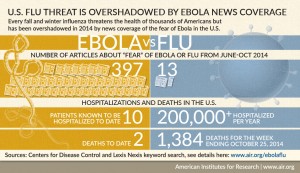

Contrast this with the lack of concern over the flu vaccine’s low effectiveness against this year’s virus, which the CDC estimates kill 3,300 to 49,000 people in the U.S. every year. Warnings from the CDC that the flu strain this year is worse and getting the flu shot will at least temper the illness seems to have had little effect on increasing vaccinations.

Ebola attracted the public’s attention with such obsessive coverage that the public expected exposed individuals to be quarantined even though an individual had no symptoms to indicate a contagious state. More importantly, contact with fluids of an infected person is necessary to become infected. Contrast this with measles where the air and surfaces an infected person has coughed or sneezed remain contaminated for up to two hours. Measles is contagious up to four days before the telltale rash appears. According to the CDC, about one in every 1,000 children who contract measles will die and 90 percent of the non-immune people close to an infected person will get it.

Fear was the driver for Ebola’s patient engagement. The measles outbreak engaged parents because it raised the issue of the high rate of non-immunized children of a highly contagious and serious disease, but there were no calls to quarantine measles victims and guard them as with Ebola victims.

The flu is an annual threat with a mortality and fatality rate that is significantly more frightening than Ebola but isn’t enough to cause a change in behavior to prevent the flu.

Gaining attention is the first step in consumer engagement. What does the public’s reaction to these diseases tell us about patient engagement?

- Fear is a strong factor in engagement. Consumers are interested in the health of themselves and their families, and a perceived threat causes action. They are more afraid of becoming ill from other people, but that doesn’t transfer to using vaccines for disease prevention.

- Consumers are uninformed or ill-informed about infectious diseases and how they are contracted. A high fatality rate such as Ebola is more threatening than a high mortality rate with the flu. Individuals naturally become alert and engaged when they are frightened. The public’s perception of health risk is skewed due to a lack of understanding of infectious diseases— the risk of infection, how they are contracted and prevented. The media contributes to the misperception of risk by sensationalizing outbreaks.

- Traditional media and social media play a big role in the speed that disease information is spread. The media hype reported fatality statistics for Africa and initially applied them to the U.S. First reports by the media failed to explain that the infrastructure of the two country’s health systems were vastly different; therefore the fatality rates would likely be very different.

- When consumers are uninformed, it is difficult to separate facts from half-facts. This can lead to chaos and panic in a crisis. There is a gap between fear and facts that needs to be filled.

How do we turn this information about consumer behavior and attention into useful steps for initializing patient engagement? Make engagement easy.

Here are three ways to start engaging your patients:

- Converse. Interact with your consumers. Social media is a conversation. Providers have the attention of their patients. Help patients separate facts from misinformation. Start a topic of interest to your patients and encourage them to ask questions that providers answer. This is the place to talk about disease prevention and health. Get a guest to write about special topics or research studies that are in the news. Write a blog and take questions and comments. Tweets are a fast way to get your opinion and thoughts out in a crisp manner.

- Educate. Disseminate curated information through provider web sites, social media—wherever the consumers and patients are. Patients trust their doctors. Use the trust to help them become informed and educated about health and disease. Providers are the trusted advisers for living healthy and disease prevention. Genetic reports based on an individual’s DNA will soon bring patients with specific questions about disease risks.

- Communicate consistently. Consistent communication between providers and patients is key to engaging patients. Interaction with patients is important to establish rapport outside of the doctor’s office. That means a multi-disciplined approach using old and new communication methods. Use different methods such as texting, blogging, tweeting to reach patients who are younger, older, high tech and no tech.

Fear of disease attracts attention for a limited amount of time — until the threat is reduced or removed. Patient engagement is about education, knowledge and choice over an extended period of time.

Fearful engagement generates chaos and is not meaningful engagement. Start the engagement process now. Waiting until the next media-obsessed infectious disease crisis is too late.